Modern life places constant demands on our nervous systems. Even when we are not facing immediate danger, our bodies are frequently exposed to ongoing stressors—tight schedules, digital overload, emotional pressure, unresolved trauma, lack of rest, and the expectation to always be “on.” Over time, this sustained stress begins to shape how the nervous system functions.

When stress is frequent or unrelenting, the body begins to spend more time in a sympathetic state—often referred to as “fight or flight.” This response is meant to be brief and protective, activated in moments of threat and then switched off once safety returns. But when stress becomes the baseline rather than the exception, the nervous system starts to lose its ability to move fluidly between states. Instead of activating and then settling, it stays on high alert. This loss of flexibility—this difficulty returning to calm—is what we refer to as poor vagal tone.

The vagus nerve is the primary pathway that allows the body to shift into the parasympathetic state, commonly called “rest and digest.” Healthy vagal tone gives the nervous system the capacity to downshift after stress, restoring calm, supporting digestion, regulating inflammation, and strengthening emotional resilience. In essence, it acts as the body’s internal brake—signaling that it is safe to slow down, repair, and recover.

In chronically stressful environments, this braking system can weaken. Over time, repeated activation of the sympathetic response without adequate recovery can lead to reduced vagal tone. When vagal tone is low, the nervous system has a harder time returning to a parasympathetic state—even when the external stressor has passed.

As a result, the body can become stuck in sympathetic dominance.

When the nervous system remains biased toward sympathetic activation, the body stays in a state of readiness rather than repair. This can show up in many ways:

- Difficulty relaxing or feeling calm, even during downtime

- Shallow or rapid breathing

- Digestive issues such as bloating, discomfort, or irregular bowel movements

- Sleep disturbances or feeling unrefreshed after sleep

- Increased anxiety, irritability, or emotional reactivity

- Heightened inflammation and reduced immune resilience

None of these symptoms mean the body is broken. They are signs of a nervous system that has adapted to prolonged stress and no longer feels safe enough to fully rest.

The good news is that vagal tone is not fixed. The nervous system is adaptable, and with the right inputs, it can regain its ability to move fluidly between activation and rest.

Restoring vagal tone involves consistently signaling safety to the nervous system, rather than forcing relaxation or trying to “shut off” stress.

Some of the most effective ways to support this shift include:

Slow, Regulated Breathing

Breathing techniques that emphasize a longer exhale help activate the vagus nerve and encourage parasympathetic activity. Over time, this trains the nervous system to recover more quickly after stress.

Vocalization and Vibration

Humming, singing, chanting, or slow vocal exhalations stimulate the vagus nerve through the vocal cords, sending calming signals to the brain.

Cold Face Exposure

Brief cold exposure to the face activates the dive reflex, which stimulates the vagus nerve and rapidly shifts the body toward parasympathetic calm.

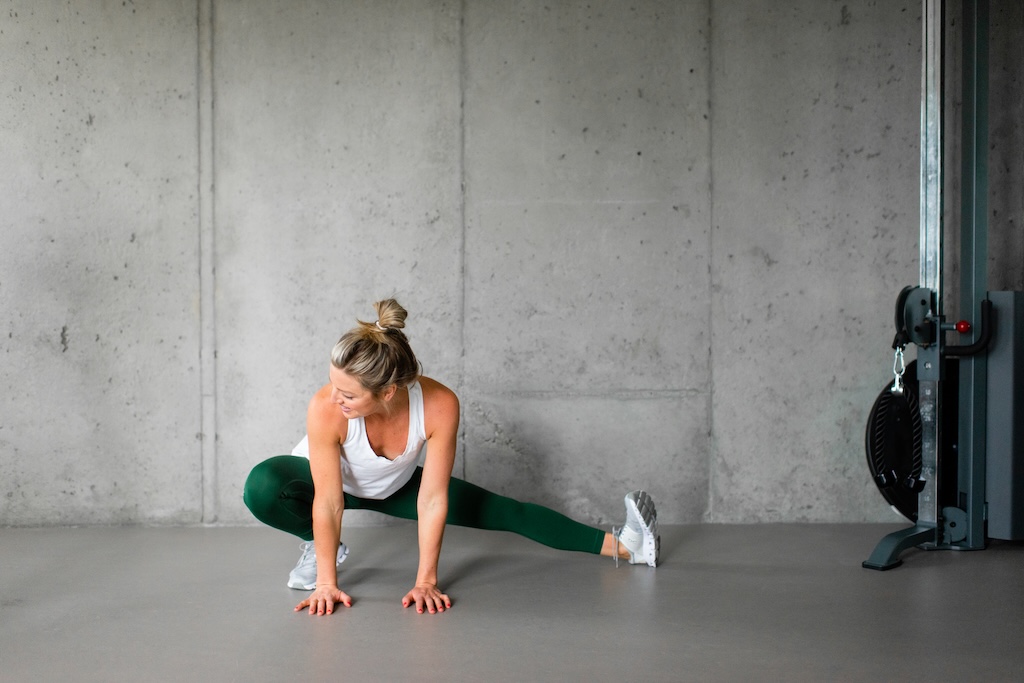

Gentle, Rhythmic Movement

Walking, stretching, and slow, intentional movement help discharge excess sympathetic energy while reinforcing safety in the body.

Mindful Presence and Emotional Processing

Practices that increase awareness of internal sensations—without judgment—help the nervous system learn that it is safe to slow down and come back into balance.

The goal is not to eliminate stress or avoid activation altogether. A healthy nervous system moves fluidly between sympathetic and parasympathetic states as needed. True regulation comes from flexibility, not constant calm.

By supporting vagal tone, we give the nervous system the tools it needs to recover, restore, and return to rest. Over time, this shift can lead to improvements in digestion, sleep, emotional resilience, energy, and overall well-being.

Healing begins not by forcing the body to change, but by creating the internal conditions that allow it to feel safe enough to do what it already knows how to do.